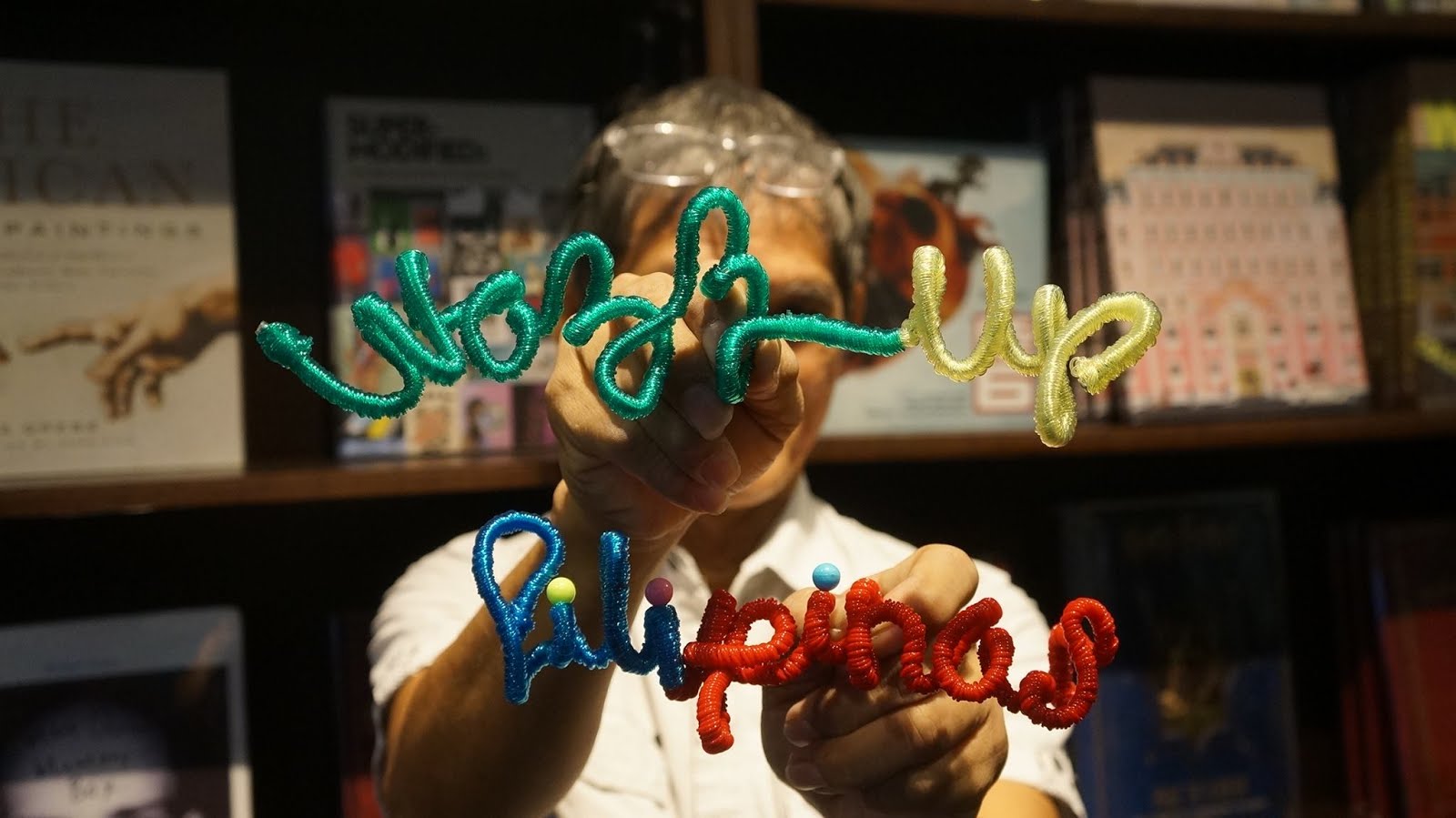

Wazzup Pilipinas!?

What are the most familiar Pinoy fruits? Mangoes, bananas, pineapples and papayas probably come to mind – but did you know that Philippine forests harbor hundreds of lesser-known fruits, nuts and herbs?

Alupag or Philippine Lychee tastes like the lychees originally imported from China. Saba or native bananas are loved by millions of Pinoys. Kamansi is our local version of Langka. Sticky Tibig fruits are produced by our native fig trees. In our mountains sprout sour berries like Alingaro, Bignay and Sapinit. And though most of the world’s mango trees originally hailed from India, we have our own indigenous mangoes like Pahutan and the fragrant Kuini.

The Philippines has strong agrobiodiversity resources. The Convention on Biological Diversity defines agrobiodiversity as a broad term that includes all components of biological diversity relevant to food and agriculture, plus all components of biological diversity that constitute agricultural ecosystems or agro-ecosystems. This includes the variety and variability of animals, plants and microorganisms at the genetic, species and ecosystem levels that sustain key functions of agro-ecosystems. Agrobiodiversity covers not just genetic resources, but the diversity of all species and agroecosystems affecting agriculture.

The pandemic and post-pandemic periods, coupled with intensifying climate change effects, have highlighted the importance of agricultural diversity and biodiversity-friendly agriculture, plus the global rethinking of our agriculture and food systems.

These new concepts now form the foundation for economically viable, resilient and sustainable agriculture. Discussing agrobiodiversity is not just about conservation and sustainable use, but about the eventual need for a systematic evolution of prevalent agricultural systems towards a more biodiversity-friendly paradigm.

Native Trees and Plants in UP Diliman

Inside the sprawling UP Diliman Campus in Quezon City lies the UP Institute of Biology and Energy Development Corporation’s (UPIB-EDC) Threatened Species Arboretum. An arboretum is a botanical garden that specializes in trees. Inaugurated in 2014, the one-hectare park features over 70 native tree species and serves two vital functions – as a gene bank for endangered trees in case wild populations drop below sustainable levels and to educate students and the greater public about the country’s native flora.

“We have so many indigenous tree species that very few Pinoys know about,” explains EDC BINHI Forester Roniño Gibe. “One of our goals is to popularize the conservation of our native plants, especially our threatened Philippine native trees.”

Though definitions slightly vary, in general, native plants naturally occur throughout a country, whereas indigenous plants thrive only in particular locales. Endemic plants can only be found in one country, whereas naturalized plants are exotic imports which have settled into new countries over several centuries.

The Philippines hosts at least 10,107 plant species, as of a 2013 study by Barcelona et al. Over 57% of the country’s plants are endemic, as per a 1996 study by Oliver and Heaney. The great majority of plants currently cultivated in Pinoy orchards, farms and gardens however, are exotic or naturalized plants originally imported from other countries.

Pineapples for instance came from South America, Papayas from Mexico, Lanzones from Malaysia. The ubiquitous trees found in many abandoned lots, like Sampaloc and Aratilis, came from Africa and Central America, respectively. Despite being called the Philippine Lemon, even the iconic Calamansi probably originated from the Himalayas.

Some native Philippine plants however, successfully broke through as mainstream products. “The Pili nut is a great example of an indigenous tree which became popular, with a following both in the Bicol Region and abroad,” explains Botanist David Ples.

Abaca, which is made from the fibrous stalks of a native Philippine banana, is another indigenous cash crop. “The key is to recognize these plants’ value and create useful, viable products,” adds David. As Pili trees and Abaca plants have become economically valuable, their survival over the next generations is assured. The same cannot be said for other Philippine tree species however.

Philippine Agrobiodiversity Resources

As per the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), biodiversity provides primary medicine for four billion people, while agrobiodiversity improves the lives of one billion undernourished people.

“Our indigenous fruits, herbs, nuts and other products can provide vital nourishment for Pinoys who might not have ready access to mainstream food. Indigenous plants also have important vitamins and minerals that are sometimes deficient in the typical Pinoy diet,” explains Department of Science and Technology Food and Nutrition Research Institute (DOST-FNRI) Senior Science Researcher Charina Javier. “However, many of our indigenous flora are neglected and underused, so their potential to provide us with nutrients is not fully utilized.”

The Philippine government has been working on the promotion of agrobiodiversity since 2015 and continues to achieve its agrobiodiversity targets under the Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PBSAP). Its targets include maintaining and conserving the genetic diversity of cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and wild relatives, increasing agricultural areas devoted to all types of biodiversity-friendly agricultural practices, the formulation and adoption of enhanced Comprehensive Land Use Plans (CLUP) using the revised Housing Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) framework which incorporates ecologically-sound agricultural land use plans and increasing the number of recognized nationally-important agricultural heritage systems (NIAHS).

In some protected areas, the encroachment of agricultural lands has become so evident that the Department of Agriculture (DA) and the Department of environment and Natural Resources (DENR) signed Joint Administrative Order (JAO) 2021-01 or Mainstreaming Biodiversity-friendly Agricultural Practices (BDFAP) in and Around Protected Areas and Promoting the Same in Wider Agricultural Landscapes.

The United Nations Development Programme’s Biodiversity Finance Initiative (DENR-UNDP BIOFIN) is currently assisting the two national agencies to enable the implementation of the JAO through by developing an agrobiodiversity framework for the country.

“We should do all we can to strengthen local agrobiodiversity, such as promoting our native fruits,” says DENR-UNDP BIOFIN National Project Manager Anabelle Plantilla. “Native and even naturalized plants can be used for a host of purposes. Alupidan and Pandan leaves can be used to garnish dishes, Batuan fruits for flavoring and Rattan vines to make furniture.”

According to the Forest Foundation Philippines, the promotion of native trees is beneficial for threatened native flora and fauna species as they help recover and expand forest habitats, protect watershed and freshwater resources, secure the livelihood of local people and link protected areas with natural forests. The newly minted Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework touches on the promotion of biodiversity-friendly practices to ensure ‘resilience and long-term efficiency and productivity’ of production systems, ensuring food security, restoring biodiversity and maintaining the steady flow of ecosystem functions and services to benefit communities.

Food Forests, where various combinations of cash-crops are planted in a natural setting, instead of the endless monocrop rows which dominate large-scale agriculture, are slowly taking root.

“Food Forests provide resilience to climate change because the cultivated crops are usually endemic and better suited to an area,” explains Muneer Arquion Hinay, Co-founder of Kids Who Farm, a Zamboanga -based initiative to get youth interested in agriculture. “They also promote better regeneration for they closely recreate natural forest ecosystems, where the symbiotic relationships of plants, fungi and other lifeforms is retained. Lastly, Food Forests can enhance soil health through improved soil cover from the leaves, twigs and natural biomass of its trees.”

At the Subic Bay Jungle Environment Survival Training (JEST) Camp, where participants learn to survive in a tropical rainforest, campers are taught how to make ‘jungle coffee’ from Kupang seeds, how to use Gugo vines as ‘jungle soap’, how to fashion survival implements from bamboo and what leaves one can chew on to help stave off hunger.

In the uplands of Sibalom in Panay, locals seasonally harvest the leaves and stems of Bakan, Balud, Banban and Nito to make tourist souvenirs, while locally-grown tobacco leaves are ground and inserted into dried Duhat leaves to make native cigarettes called Lomboy or Likit. Local knowledge is already boosting forest productivity.

“The United Nations Development Programme promotes ethical, natural ways not just to produce food and other vital resources, but to find alternative livelihood opportunities for communities living in or near forestlands, and that are supportive of the UN Sustainable Development Goals,” adds UNDP Resident Representative to the Philippines Dr. Selva Ramachandran.

Established in 2012 and with a network comprising 41 countries in Africa, Europe, South and Central America, plus the Asia Pacific Region, DENR-UNDP-BIOFIN helps raise funds for smart agriculture to boost the productivity of ecosystems, while repurposing potentially harmful agricultural subsidies into effective conservation measures. In the Philippines, BIOFIN, the DENR and DA are developing an agrobiodiversity framework that will integrate all related PBSAP targets and include a stocktaking of potential agricultural subsidies that either enable or erode biodiversity.

“Our forests serve many key functions. They provide habitats for wildlife, generate the oxygen we breathe, even offering us places to spiritually recharge,” concludes Anabelle. “We can make them worth more than logs or farmland by seeing them as our First-Nations people have for generations – as a pharmacy, a grocery and an extension of our home.”

Visitors interested in learning more about native Philippine trees, fruits, nuts and herbs can schedule a visit via Facebook to the UPIB-EDC Arboretum in UP Diliman, where donations for upkeep and maintenance are appreciated. (ENDS)

About the Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN)

BIOFIN was launched in 2012 and seeks to address the biodiversity finance challenge in a comprehensive manner – building a sound business case for increased investments in the management of ecosystems and biodiversity in over 40 countries, with a particular focus on the needs and transformational opportunities at the national level. For more information: http://www.biodiversityfinance.net

About the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

UNDP partners with people at all levels of society to help build nations that can withstand crises, and drive and sustain the kind of growth that improves the quality of life for all people. On the ground in 177 countries and territories, we offer a global perspective and local insights to help empower lives and build resilient nations.

In the Philippines, UNDP fosters human development for peace and prosperity. Working with central and local governments as well as civil society, and building on global best practices, UNDP strengthens the capacities of women, men and institutions to empower them to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the objectives of the Philippine Development Plan. Through advocacy and development projects, with a special focus on vulnerable groups, UNDP works to ensure a better life for Filipino people. For more information: https://www.ph.undp.org

Pili Nuts (Canarium ovatum) are among the most successful ‘Forest Foods’ – having reached mainstream acceptance as both a local and international delicacy. Because of economics, high-value crops are usually safe from extinction.

Pahutan Mangoes (Mangifera altissima) are native to the Philippines. They are not often grown commercially, but are harvested in bulk from the wild.

The Rattan (Calamoidea) family hosts over 600 species, with many bearing edible fruits. These were gathered at an upland forest in Leyte and tasted sour, but palatable.

A basketful of forest goodies: native Alupidan (Tetrastigma harmandii) leaves, spicy Siling Labuyo (Capsicum frutescens) and sour Batuan (Garcinia binucao) fruits arrayed for the creation of a native dish called chicken Porbida, which has been made in Panay since the Spanish introduced it in the 1600s. All these can be grown in a ‘Food Forest’ which recreates natural systems.

The Abaca Plant (Musa textilis) is actually a type of banana native to the Philippines. Its stalks have been used for making textiles and sturdy rope since before the Spanish era. Endemic flora provides not just food, but other useful products.

Called the 'Food of the Gods' and treasured by ancient civilizations such as the Mayans and Aztecs, Cacao (Theobroma cacao) originated in Tropical America but has since spread throughout the tropics. Though used mostly to make chocolate, the fruits also actually taste quite good.

Lomboy or Likit are native cigarettes made by wrapping locally-grown Tobacco Plants (Nicotiana spp.) in dried Duhat (Syzygium cumini) leaves. Though not native to the Philippines, these naturalized plants have become Philippine cash crops. Likit cigarettes are commonly smoked in the hinterlands of the Visayas.

A Kupang Tree (Parkia timoriana) with its wall-like buttress roots frames UP Institute of Biology’s David Ples, EDC’s Soleil Acu and Abigail Gatdula, plus environmentalist Gregg Yan at the UPIB-EDC Threatened Species Arboretum in UP Diliman. Seeds from the Kupang Tree can be crushed and roasted into ‘jungle coffee’ which is bitter but has zero caffeine.

The UPIB-EDC Threatened Species Arboretum can be found inside the UP Diliman Campus in Quezon City. Inaugurated in 2014, it hosts over 70 native and endangered tree species. Visits must be coordinated with the UP Institute of Biology beforehand.

The JC’s Vine (Strongylodon juangonzalezii), a rare jade vine which features magnificent purple flowers, is one of the arboretum’s star attractions. It is currently in full bloom at the UP Campus.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.

Ross is known as the Pambansang Blogger ng Pilipinas - An Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Professional by profession and a Social Media Evangelist by heart.